The Ranch & the First World War

2014-2018 marked the centenary of the First World War. 2018 specifically saw the 100th anniversary of major Canadian battles, such as the Hundred Days campaign. Read on to learn about the First World War's impact on the Okanagan, or skip below to see some of our First World War artifacts and documents.

Turning Points

British Columbia’s contribution to the war was immense—about half of the initial recruits signed up in Western Canada. Many soldiers who enlisted in British Columbia trained at the army camp in Vernon, which swelled the city’s population and brought the conflict closer to home. The presence of the war on the home front was intensified by the establishment of an internment camp in September 1914, imprisoning hundreds of German, Ukrainian and Austro-Hungarian so-called “enemy aliens.”

The First World War was a turning point for the O’Keefe Ranch. An economic depression swept through Canada in 1914, and Cornelius O’Keefe’s successes in the late 19th century were overturned in the first decades of the 20th. The O’Keefe Family shared the wartime experiences of many other Canadians—sending their sons, brothers and husbands to join the fight, while trying to keep up morale at home.

“If ever a country wanted war it was Canada in that week.”

– G.R. Stevens, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry

War Is Declared

When Britain declared war on August 4, 1914, dominion nations like Canada were automatically brought into the conflict. Canadians were excited by the prospect of war and wanted to defend the British Empire—many of the first recruits were recent immigrants from the United Kingdom. The Great War—as it was christened within days—also represented an opportunity for Canadians to gain employment after years of economic depression. Some believed it would be a great adventure, and most assumed the war would be over quickly.

Sir Sam Hughes, Canada’s Minister of Militia, was tasked with recruiting Canadian troops. In 1914, Canada had a military force of about 3000 regular soldiers and a militia force of about 65,000, out of a total population of 7.2 million. Hughes believed that volunteer soldiers were much more effective than regular standing armies, and sent out a call to Canada’s 296 militia groups…

“When the news of war came, we did not really believe it! War! That was over! There had been war, of course, but that had been long ago…”

– Nellie McLung

Camps Are Made

The initial attempts to establish a North Okanagan Militia Unit dated back to 1884, and one of the early supporters was Cornelius O’Keefe. However, it was not until 1908 that a militia was formed in Vernon, with branches in Lumby, Coldstream, Armstrong and Enderby. In 1912, a summer training camp was established in Vernon that brought soldiers out from all over British Columbia. By 1914, when Sam Hughes made the call to Canada’s militia units, the 30th B.C. Horse from Vernon answered.

In 1915, a recruiting tent was set up at the summer training camp on Mission Hill. That May, with less than two weeks of preparation, the site was made available to train BC’s soldiers. Vernon, whose prewar population was about 3000 people, was soon joined by 7000 soldiers.

An internment camp to house so-called “enemy aliens” was established on September 18, 1914 in a former mental institution. It is difficult to know how many individuals were interned in Vernon, but 8,579 were interned all over Canada. The Camp in Vernon was not closed until February 20th, 1920, almost two years after the war ended.

“We have had some warm times but I am quite unharmed, but I am afraid there will be many sore hearts in Canada by the time this reaches you.”

– James Wells Ross, April 25, 1915

Everyone Enlists

Between 1914 and 1918, approximately 710 men from Vernon enlisted for war, accounting for more than 20% of the population. Thousands more from the Okanagan enlisted, including three of Catherine and Augustus Schubert’s grandsons. Bertram signed up in 1915, and was followed by his cousin James in 1916. James had lied about his age (he was 16), and was later sent home for being too young. James’ brother Dudley joined up in 1916, having lied about his age as well. His attestation paper lists his birth year as 1897, but he was born in 1899. Dudley had just married Lily Maude Tooley in 1915 (he was 16 and she was 17), and the pair had their first child on September 7, 1916.

Other parents, like Price and Sophie Ellison, saw each of their sons enlist. As the Vernon News reported on May 5, 1917, all four Ellison boys were in uniform.

Okanagan First Nations men from the Head of the Lake signed up in record numbers: every single eligible man aged 20-35 enlisted during the war. At least fifty Canadian First Nations soldiers were awarded medals for accomplishments and bravery during the war. One such soldier was George McLean from the Head of the Lake, who single-handedly captured 19 German prisoners during the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917 and earned a Distinguished Conduct Medal.

Many Canadian recruits were British-born, and signed up for service with the British Expeditionary Force. Captain J.C. Dunwaters, who arrived in the Okanagan in 1909, travelled back to Britain upon the outbreak of war to serve with the Middlesex Yeomanry. He fought in in Italy, Gallipoli, France and Egypt, and returned to the Okanagan in 1919.

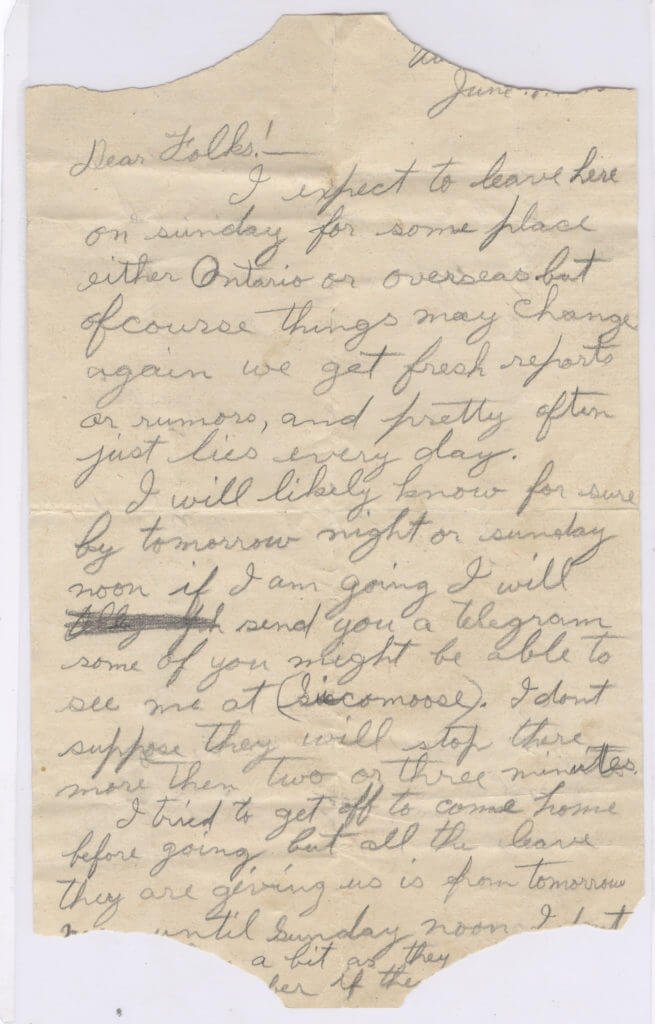

“I expect to leave here on Sunday for some place either Ontario or overseas, but of course things may change again we get fresh reports or rumors, and pretty often just lies every day.”

– Roland “Rollie” Hayes, June 1917

The Military Service Act

Agricultural workers made up one of the largest proportions of labourers in Canada in 1914—about 30% of the population. While most ranch and farm workers earned about $1 per day—less than working as an infantry soldier—O’Keefe Ranch records show that employees earned between $2 and $2.25 per day.

In 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden invoked the Military Service Act—conscription for unmarried men ages 20-35. At first, this exempted farm workers because they produced food for Canadians at home and abroad. Within months, however, the exemption was lifted and agricultural workers like Roland Hayes (a neighboring farmer who knew the O’Keefes) were subject to conscription. 24,000 conscripts made it overseas. In 1918, the Canadian Food Board organized a national initiative called Soldiers of the Soil—a program for boys aged 15-19 to help on farms so that agricultural workers of military age could join the fight.

“I hear that Austria has made peace with the Allies and that the latter are driving the Germans headlong out of Belgium.”

– Cornelius Jr. “Connie” O’Keefe to Ranch Foreman, Jack Cousins, October 1918

The O’Keefe Family

The O’Keefe Ranch, which enjoyed great success by the 1890s, had since downsized. Cornelius O’Keefe sold much of his property to the Land and Agricultural Company of Canada in 1907, and spent his “retirement” developing movie theatres in Vernon and Kamloops. The Ranch continued to operate, but on a smaller scale. Still, Cornelius O’Keefe’s family was very large by 1914—he had 14 surviving children after three marriages.

Each member of the O’Keefe family experienced the war in their own way. Helen O’Keefe’s husband, Captain Herbert Dawson, enlisted in 1915. He died during an attack on an electricity generating station in Northern France on June 4, 1917.

Thomas Leo O’Keefe joined up in 1915, followed by his brothers Francis in February 1916 and James in March 1916. All three were experienced marksmen, having learned to shoot as young boys on the Ranch. Thomas Leo and James survived the war but Francis fell ill with pneumonia at a training camp in Kamloops, and died on March 21, 1916.

Cornelius O’Keefe’s grandson, Johnny Harris, enlisted in 1917. He fought in major battles like Passchendaele and Amiens, but was fatally wounded on August 15, 1918. Johnny left behind a wife and two young children.

Cornelius Jr., was only 13 years old in 1918, when he noted the spread of influenza throughout North America at the end of the war. Four students died at his school in Washington State.

In May 1919, just months after the war ended, Cornelius O’Keefe died. His family carried on the family business until 1967 when the 100-year old Ranch was opened as an historic site.